|

Wednesday, July 7, 2021

Teasing Board

So, you are mighty proud of your alpaca. He or she has taken his or her halter class and then you entered the fleece in a show and it did well there, too. So, that’s great. But how much do you really know about this fleece? So, I am issuing a throw down to all of those that both show and sell fiber products. Select one fleece that you would be willing to hand process at home and make a few hours each day available in order to make spinning batts of this fleece. If you are as busy with barns and herd health maintenance as I am, this may only be a few hours each day, but I guarantee you will learn a great deal about your fleece.

I have a boatload of fleece that I need to start sending out to mills. I have skirted and done an initial “sort” as to grade of each fleece. But since I ran out of nice alpaca to spin on my group of e-spinners as well as knowing the wait time on receiving processed fiber from mills, I decided to select a fleece I really love and a male that did extremely well in the show-ring. As a fiber sorter, I had looked already at six samples taken from withers, mid-side and stifle on both sides and examined these for tenderness, staple length uniformity, essential grade, presence of strong primaries, type of fleece frequency, and I had skirted the fleece. It’s a large, weighty fleece for a light silver gray. Is it my most elite fleece on the farm? Since I have pursued elite whites here since 2002, it’s not the most elite but it has many excellent qualities, and extremely uniform fineness.

I am one of those who does not believe in washing fleeces necessarily. Here are my tools I employ to hand-process a fleece. I have a teasing board. A lot of drum carders come with them, and you can buy teasing boards. They come with a C-clamp so you can clamp them to a table. If you prefer you can always use a dog flicker brush to clean fiber, but the teasing board is my preference, as I can run a group of staples through cut side and tip side and on both sides, and the teasing board stays in place. I have an idea in my mind of what is the best size in terms of groups of staples so that I have less waste and when finished I have exactly the size of a staple that would go into my drum carder without overloading. You can see a picture of my teasing board in the images provided.

It’s a pretty basic thing, but working from the tip side of a section of the fleece (I prefer to work with sections of the fleece), I pull my group of staples. I firmly grasp the center of the group I have pulled and twist once to ensure I have a firm purchase on the staple, then comb it tip side first through the teasing board on that half, then turn it over and comb again on the other side, then reverse the staple in my hand and do the cut end, again, both sides. Now, rest assured, you will have a lot of dirt and you will have some waste. In fact, you will appreciate the “shrinkage” that your mills you deal with see from doing this exercise. When I pull the staples, if there are “fuzzies,” which are cross fibers, I pull them and place them in the waste category. Yes, I realize I could be pitching some very fine fiber but when teasing the fiber, these fuzzies are going to wind up on the teasing board anyway.

Okay, you may also run into a particularly FILTHY part of the fleece and it may have absolutely GORGEOUS architecture, but if it truly is too dirty – and you can see this because the cut side is just as dark with dirt as is the tip side – this will not yield a clean fiber that you would want to spin! Throw it out. If you just cannot bear the thought of throwing away such beautiful stapled and organized fleece, then be prepared to clean your teasing board very often! So, your guy likes to cush in dried manure piles before you or your help can get out to rake it up. That is life. I should mention that my animals are bedded inside the barn on screened sand with high calcium lime mixed in to combat any nasties. Our paddocks are sandy and it means when I dry lot animals, they really are high and dry! Only when we are expecting zero or subzero and windy conditions do I lay out straw around the areas where my animals congregate. I take it up once weather normalizes. I also am a bit OCD when it is six weeks away from our shearing dates, so any dropped hay, whatever, is cleaned up in all pens at that time. So, most of what I am cleaning in the teasing process will be a sandy residual and VM aka vegetable matter. If you deep bed your alpacas during winter and do not clean for six weeks prior to your shearing date, you might not be able to process a fleece as I am describing.

As I go through a fleece, I take a section at a time for processing. Here is a good-sized section that I pulled out the other day. While I did not take pictures of a sample staple, I take about five staples at a single time. You should not be making a Herculean effort to get your staples through the teasing board. I find there is less waste when I tease smaller staples and the benefits are that the staples are about the right size for inserting into your drum carder at one time (see below).

Even though you have assessed staple length, both the process of shearing and other things will cause you to reevaluate consistency of staple. I am talking blanket fleece only here. On neck fiber, while many animals have amazing neck fiber of the same quality as that of the blanket prime fleece, rarely is staple length likely to approach that of the blanket so, were I to be making spinning batts from that fiber, I would make them separately. I prefer to keep shorter staples for making separate batts. In fact when I find perfectly wonderful but shorter staple blanket fiber I separate it out so that my batts are as equivalent in staple length as possible.

So, then, I put the staples through the drum carder. I use a motorized drum carder and my drum has the highest TPI because I only process my finest grades at home. I bought a model for which you can buy lower TPI drums and switch them out with ease, just in case I decide to process a more robust grade. For awhile, I held onto my original hand crank carder thinking I might need it to do a fleece more slowly, but I discovered that the speed dial on my motorized carder can go more slowly than I could ever do by hand crank, so I sold my hand crank drum carder. If you own a drum carder, you probably have heard the wise old adage that you ought to not put any more fiber into the carder at one time unless “you can still read the newspaper through the fiber.” If you are teasing locks in the appropriate amount, even if you have a huge bag of them, they do tend to stay in the teased staple and so, problem solved as to how much to add. I wind up with batts that weigh about three to four ounces. Yes, I would love to upgrade to an extra wide drum carder. A picture of my drum carder is shown in the images.

I have included an image of a single completed batt and a bag full of spinning batts in the images section. Now, I prefer to put a batt through a second pass. So, I rip the batt into maybe five strips so that what is entering is not going to be too much for the carder to handle.

Now, I don’t have a mini-mill and I have tried washing fleeces before (and I will do so if I am doing contract work for other farms), but because most of what I am trying to clean from my fleece is sand, I get it very clean indeed. And let’s face it. When handspinning, we all wash skeins to set the twist. Just provide full disclosure to your customer as to your method. Once they feel your end product, I think they will be more than happy with the result.

So, what are the takeaways from this exercise?

• Appreciation for mill owners whose services you employ. You learn about the great lengths your mill owners go to return to you clean and usable product, even though you skirt it beforehand.

• Fleece anomalies that a six sample initial sort will not provide you. You might discover a tender spot in a fleece and, whether the result of shearing or otherwise, you might find some that staple uniformity is not as perfect as you think.

• Now, if you are a handspinner, take a batt and try spinning. There is nothing better than knowing that your hard work resulted in something you can enjoy turning into yarn!

When I complete this fleece, I expect I will have upwards of 25-30 spinning batts. Now, if you are adept with a dizz, you might be able to dizz your batt off as roving. I just spin directly from a batt but your customers might prefer to spin from roving. And yes, there is a great deal of fleece that winds up on the processing floor, but ask any mill owner about that. Oh, and another thing I learned. I like doing this. I don’t refer to myself as the “control freak fiber artist” without reason! So, I think I will select yet another fleece for this exercise when I am done with Nick’s fleece.

Drum Carder

Section of Raw Fleece

Finished Batt

Bagful of Spinning Batts

|

|

Saturday, August 19, 2017

Ben Franklin had it right, right from the start. Did you know our early coinage had the words "Mind Your Business" on them? Well, they did. An astute businessman if ever there was such, Franklin meant business when he used the term!

How does this relate to alpacas, you might ask. Well, since I have been raising alpacas for twenty years and counting at this point, it means a lot to me. First of all, except for the examples at zoos, alpacas did not start entering the US until the mid 1980s. Llamas did come earlier, but even then, when you consider camelids and what we really, really know about them, we just have not had them in the US for all that long and the very small percentage of camelids that were in selective breeding programs with extensive care protocol in South America needs to be kept in mind. Those of us that have made the conscious choice to have these animals in our barns, paddocks and pastures need to really get to know as much as we can about our choice of livestock. When I entered the business, there were very few texts on camelids, but I acquired all of them, including the out of print book called by one and all "the alpaca book." Fowler's Medicine and Surgery was out there as well, so it wound up on my shelf. I went to sheep sites and acquired books related to parasitology and some handbooks for shepherds. There were a few really good texts on goats, so I bought them as well. Now, we do have a great deal more research that has been performed. We even know that blood serum "norms" for camelids are not the same as those for normal small ruminants, thanks to an extensive study in the Pacific Northwest conducted by members of the faculty at Oregon State at the time. It is said that the best investment portfolio managers are as good as they are because they read everything they can get their hands on -- it is incumbent on camelid breeders to do nothing less. Now, I have to admit, the internet has improved, particularly in terms of depth of content, such that we can keep pace and read about latest studies being conducted. Now, there is no substitute for hands-on learning from someone with far more experience. Mentors are gems and most of those of us that have served in this capacity view mentoring as a gift -- in schooling new market entrants, we are creating another colleague who we can bounce ideas off or learn from in the future. Well, at any rate, that is how I view mentoring, and regardless of what business I have been engaged in, I have treated mentoring in that same way. My former students in the investment world have taught me much over the years!

I am the first to say I am in awe of large animal vets who switch gears with each and every different farm they visit. That said, even if they attended a veterinary college that had a herd of camelids or even had a camelid studies program, it is paramount that they emerge from their programs as generalists or they would not be able to perform their job as they do. Hence, WE the breeders of these animals are the specialists. We see them daily, we know who is feeling off just by scanning the barn, provided we really do know our animals. I know that the vast majority of us do everything we can to know these animals. After all, their stoicism when they are not feeling well is famously known for making them quickly go downhill when they can no longer keep up their pretense at being "just fine."

All this is to say, when you have an issue at your farm, by all means contact your veterinarian and consult with him or her. The information is valuable! However, if you see things differently and your colleagues who also spend all their time focused on these animals echo your sentiments, it is best to follow your instincts on the course of treatment. I am not advocating administering medications that your vet does not feel are appropriate for the animal, but in minding your business, you have to consider what is best for that animal and your herd and be that specialist that is well-read and well-versed in the quirks of each individual in your herd.

|

|

Sunday, June 18, 2017

Man In Motion, Dam Nuzzling

Well, as I write this, our farm is in the full throes of farm babies. My brother secretly allowed all his Toulouse geese to set eggs -- as if I would not notice, mind you -- and all of a sudden I heard the peeps coming from the antique barn and then the cutest goslings were running hither, thither and yon. My Royal Palm turkeys have no poults as yet, but they figured out the egg sitting business, and my Tom is basically the main egg sitter! So, I suspect we will see poults hatching naturally. I had given up on the possibility of naturally raised and hatched poults this year and had bought an incubator. It now seems superfluous.

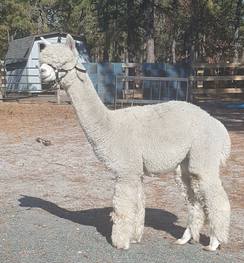

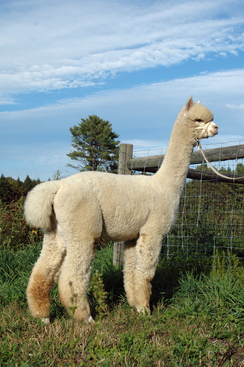

Today, we had our first cria of the season. As every alpaca breeder knows, the first cria is always the "cutest" thing, period. The dam is one of my oldest home-grown females, sired by my import B-line Accoyo male, Powerball. She was left out of the line-up for quite a number of years, as I was breeding her champion daughter for one thing, but then I realized that, if I wanted to achieve a line-breeding of the most powerful dam to ever grace my farm that Quarterback Princess, who is a granddaughter, was just the ticket to breed to my most famous home-bred and born male, Hidden Hill Peruvian Dually, himself a son of the same awesome dam. Now the dam in question was CP Chilam and, with the exception of her first cria born to me, who I sold once she had produced Quarterback Princess (figuring I would probably get another Chilam daughter -- hah), all I ever got from her were the most phenomenal MALES. So, why should I be one bit surprised that, in this dam line breeding effort, Quarterback Princess rewards me with the first male she has ever produced. Chilam, you are laughing at me from those golden pronking pastures -- and I know it. It's okay, though, as Man In Motion appears to be another gorgeous male. But my high praise for older females is, quite simply put, this: you know these girls, and you know their ways. Most of them do NOT want your assistance in anything. In fact, I was busy cleaning the barn, refilling the hay feeders and just starting to feed out the morning feed supplement when I looked out into the paddock -- and there was a cria, sac hanging all over it, walking around! I slipped into the paddock from a side entrance, and dipped the navel. I then finished putting out the feed, got my brother to help me set up a bonding pen in the center of the action for socialization reasons, and opened the door and let everyone in. You can get a good mom to follow you anywhere -- just pick up the cria. Quarterback Princess followed me into the bonding pen, in spite of the distraction of the morning feed ration! I tried introducing the kid to mom's udder but QB would have nothing to do with THAT! Silly me, she does it HER way! So, I went back to the farmhouse to get another cup of coffee, as I should know by now that QB is a total DIY dam, and face it, that is easier on all concerned. By the time I went back up, she had expelled the placenta and had taught the little guy to nurse like he'd been doing it for months.

So, for all those who sell off those tried and true-blue older gals, I can only say this: someone else will benefit from having a female that knows just how it's done, and maybe those "new models" you buy to replace them will do a great job, too, but you won't know that until you see them at work. Now, I am not advocating holding onto totally unimproved females, simply because they are great dams, particularly if you do not think you would want a male from them (that is the acid test, really -- if you don't want a male from a female, then sell that female; okay, you keep them if you are in the business of doing ET maybe) but in the case where you have a proven female -- especially one that is emblematic of your own program -- and she has the goods to make top quality cria and you have a history of how she will deal with a birth, those girls are GOLD in my book.

Man In Motion, still wet

Dam, Not Too Typey but...

|

|

Saturday, June 10, 2017

We all were there once, and the memory of those days has yet to fade from view, even though I have been raising alpacas for twenty years. I wrote this piece originally as part of a new breeder package I used to hand out but, with all the people buying online, I figured a rework of this piece was in order and adding it as a blog made sense as well.

There is nothing more important than the selection of your first foundation female alpacas, and no one will know exactly what you need better than you yourself will. That being said, I encourage you to visit as many farms as you possibly can squeeze into your hectic schedule before you buy one single alpaca! Get your hands on animals, get to know what a straight topline actually feels like, what straight legs and proper carriage is all about. Watch an animal that catches your eye walk around, follow its movements. Make sure, if you are not offered it, to ask to see the bite on an animal. Learn as much as you can about fiber -- attend seminars that will help you learn about the industry and about fiber. Even though you may think that, since we have been in what is called a “buyers’ market” since 2008, it's not that expensive to make a few "beginner's mistakes," you still need to be thrilled with what you buy and as educated as you possibly can be about the female or females you are considering – and you need to have a clear idea of what your breeding goals are as well. After all, it costs as much to feed a mediocre animal as it does to feed the best animal you can afford to buy. I strongly encourage prospective new breeders to keep looking and asking questions of the breeders they are visiting, until they are confident enough in their own ability to stand in a pasture, look at fifty females, and point to one, two or three and know those are the ones they want to examine more closely. Over time, you will develop in your mind's eye, if you take the time to learn as much as possible and observe well, a picture of your personal alpaca ideal. In an industry which, rightly or wrongly, does not have a breed standard it is important that you develop one of your own. Even though there is work being done on a breed standard at this time, I can assure you that, having had my own for a long, long time means that whatever is proposed and ratified by the AOA BOD will not alter the way in which I do things at my farm. At the same time, be prepared to get all the necessary information to ensure that your budget will not only provide for the animals but for their proper care and accommodation.

As anyone engaged in livestock breeding will tell you, there is only one time when you can select for multiple characteristics, and that is when you are acquiring foundation stock. Once you bring that animal home, you are challenged to select for one specific characteristic. Thus, the more you know prior to selecting foundation stock, the better equipped you will be to make informed decisions that can affect your breeding program for many years to come! After all, if you bring young females home, they will be in your pastures (unless you sell them) for twelve to fifteen years. I have females I selected as weanlings back when I started out that are in their teens now, and those tried and true-blue females still produce elite, banner-winning results for me.

Bottom line, I would suggest starting out with bred females, or young maidens that have reached the age when they can be bred -- that way, you can actually select the breeding, particularly if you are buying from someone who has a variety of top-quality stud males. Now, when buying bred females, pay close attention to the stud male used to breed them. Is he available for view? Does he have cria on the ground that prove his ability to throw quality? Show ribbons are nice, but there is nothing like living examples to afford you an opinion as to the ability of this male to reproduce his type and improve on the females presented to him. Does he have any particular faults that are also present in your female -- in effect, will waiting the eleven plus months make sense? Some traits are more heritable than others, too. Conformation (or correct physical structure), for the most part, has a very low coefficient of heritability, so if you cannot breed for it, the best you can do is ensure that your females and the males to whom they are bred all possess correct physical structure. Even if an animal possesses a certain positive trait, being able to see his offspring will give you some idea of whether or not he can reproduce that trait. I consider genetics offered by the male a very important element, but remember, the very best "upgrade male" in the world will only be able to do so much. I like to tell new breeders to buy a female from which they would be thrilled to have a male. Then, add an awesome male into the mix that complements all the good aspects of your female and has areas of strength that your female lacks, and you are doing the best that you can -- this is livestock breeding after all, and there is an element of surprise, both good and not so good, involved. Time becomes one of the biggest cost inputs to alpaca breeders -- there is nothing free about a "free breed-back" if it is to a male that does not have strengths to counter the weaker points in your female. Believe me, all females, no matter how ‘elite’ they are, have weak aspects that can be improved. I can also say that there is a whole separate discussion to be had about seeing both parents of a female you are seeking, too, but I will leave that for another discussion. When seeing the male, you should ask the owner what he/she would change about him. Here again, no matter how celebrated, there is no perfect male with nothing that could be changed! With respect to males, I do counsel new breeders to really defer on purchasing a stud male -- the economics is simply not there at the outset. A lot of people tend to buy a male the minute that first adorable cria hits the ground, if not before that. It is understandable not to want to see that cria disappear onto another farm for a two-three month period during its "maximum cuteness phase," but a lot of us that own numerous stud males are offering drive-by breedings and are set up with proper biosecurity in place to accommodate that, and also are prepared to do mobile breeding as well. Find out what top genetics are available in your neck of the woods -- with all the ownership participations in top quality males that abound, there is no doubt you will find local breeders that have genetics that will enhance your herd.

Independent pre-purchase exams are absolutely recommended for any purchase, in my opinion -- if you are buying a bred female, the pre-purchase exam should include re-confirmation of the pregnancy, preferably via ultrasound. Some breeders offer this as part of the purchase but, even if they do not, if you carefully read most purchase contracts, you will see the wisdom in having a pre-purchase exam performed – and paying for it yourself. There is nothing “independent” about even the most independent veterinarian performing a prepurchase exam if the Seller is paying for the exam, no matter how generous that offer appears to be!. Make sure that the veterinarian the Seller refers you to does not have a business relationship with the Seller, as you want there to be no conflicts of interest with respect to buyer or seller. You also should be paying for the exam for the same conflict of interest reasons! Now, it is worth bearing in mind that a veterinarian can only opine as to specific things such as no deformities of limb, anatomical parts but when venturing into proportion/carriage/balance or FIBER issues, you the Buyer must have the final say.

If you are still searching for a farm or have a barn to build, or fencing to put up, the breeder should be able to work with your schedule and offer some partial free board.

|

|

Monday, June 5, 2017

Well, it is now June (please, please tell Mother Nature, if you have her ear, as I am tired of wearing a winter jacket to do my barn chores), which means breeding season is upon us here at Hidden Hill Farm Alpacas. Ideally, by now I would have submitted all my fiber samples so that I can assess the 2016 cria crop but, being a fleece sorter, I know a lot already. Regardless, statistics can give us a great deal more with which to evaluate animals.

On shearing day, I collect that prime blanket fleece as it comes off each animal and, even if I had someone to do it for me, I think I would prefer to be there. You might ask why. Well, I can see a great deal about fleeces, not only on my young animals but on my mature foundation stock, just by how that fleece comes off. Is it in one solid piece regardless of how the shearer's "head guy" turns that animal, is staple length hanging in there, is pulling a fleece sample more difficult or does the sample just fall out in one's hand? Are there extending primaries? I have scored my animals on this basis, in addition to the more holistic scoring system I employ, and it is telling indeed. In fact, some of my best foundation females whose fleeces still exhibit all the qualities I would seek in a young prospective foundation female, are over ten years old! Yes, you read that right. Now, I probably have five or six females that I have bought that are in my foundation herd, and the rest were produced from my program.

Every breeding here is carefully calculated. I want to know that what I produce will be a keeper. Is it all the harder to sell those keepers? Well, yes, it is, to a degree. Selling one's best is not easy! I am going to be asking the potential buyer many questions about how they plan to use those animals. After all, these could be the future of one's herd, if all the homework one puts into the task of ferreting out the traits of each female and selecting just the right male to enhance that trait or traits (only if they are highly correlated can you even consider trying for multiple trait improvements) that you have selected as well as allowing that female's best qualities to be fully expressed. I have about forty elements by which I score an animal and, since I do herd evaluations for other breeders, I finally had to codify those elements, so I actually have a spreadsheet I can employ. Having bred alpacas for twenty years now, it is quite a simple matter to process a great many elements mentally when evaluating one's own females, and the process is so swift that it takes time to slow down and consider what the variables are that one is seeking. Now, I know there are people that use one male over an entire herd. That is fine, but my question to those that do this is: what are your chief complaints about the females in your herd? Are they all focused in one particular trait, or is there a fairly decent litany of things you would like to see in each, all of which vary by the female in question? If so, I would contend that there is no silver bullet male that can "fix" everything in such a herd. If that male were to make a substantial improvement on 15% of that variable herd, I would say you have quite a male on your hands! Now, if you are employing a traditional livestock model and are willing to wait for generations of offspring, then using a "herdsire" (which is a term that really only ought to be used when you are putting that male over all of your females) may be the way to go. With a little over thirty breeding age females here, I breed fifteen to twenty per year. I consider myself to be a trait breeder for that reason -- and for the reason that I breed for keeps, regardless of whether or not I sell an animal.

Truthfully, I have very few traits that I am honed in on, even among my thirty or so females. I consider some to have far more "advanced" fleeces and some of these also seem to hold onto desirable fleece characteristics longer than others. I take note of any pedigree correlations when I make my notes from shearing day. However, this is the extent to which variability plays a role in my program.

Well, I never know when I am going to sit down and write a blog for my website. I guess today was one of those days.

|

|

Thursday, October 6, 2016

I think I do most of my thinking when I am working in my two alpaca barns. So, here are a few "off the top of my head observations" from the last couple of days.

If you want to be known for your stud males, be known for the quality of your dams. Now, this really is true. New market entrants go through a couple of phases, including the "research phase," the "build-out phase," and then the "build from within phase." Whenever I meet someone in the "build-out phase," I try to advise them that there is an important interim phase called the "take stock phase" when it is wise to cool one's jets, stop acquiring and see what those dams can produce for one's program! I am confident that those that do not allow for a "take stock" period could be doomed to repeat their build-out phase. Now, I am not sure that some ever achieve the "build from within phase," to be perfectly honest. It was a long-term goal of mine to produce my own dam lines here, from my original foundation herd. I did achieve this, and I still wince when I sell a female that I am certain would be the perfect replacement for her dam, but I still believe in selling my best. Admittedly, I was a bit of a hoarder at one time, but learning to let go and allow herd improvement to be passed on to one's customers takes some time but it pays dividends. There is a common misconception that, if you do not keep buying to upgrade your herd, you can fall behind the curve. While there could be a degree of truth to this, if everyone were trait breeding rather than trying to pile on as many big-name males as they can muster, I tend to believe this is, at the very least, a partial fallacy. Herd improvement, TRUE herd improvement, can only be achieved if a person carefully scores dams and then selects a male that will not downgrade any of the dam's best features but might hone and enhance a trait or two where the female could be upgraded. Admittedly, there are other herd improvement models that take far longer to have an impact. I have one question for those that hold to this premise of constantly buying to "stay ahead of the curve:" if Caligula, Bueno and Hemingway were still alive and you were offered the opportunity to breed to them, would you? Too, there have been import dams who have had such superlative production records that, while they might have made a replacement offspring, when you lose one of these import girls (and I have), you feel that loss very acutely.

The waiting is the hardest part (apologies to Tom Petty). Okay, we wait 11.5 months (or more) for a cria to be born. If you do elite lights, you might also talk about having to wait for the "second fleece." I cannot tell you how many people have offered me females that "just don't have the fleece I was looking for," only for me to be the beneficiary of knowing, based on architecture, that this animal would be burning up the show-ring as a yearling. Then, there is the question of when a female is ready (or a male, for that matter). When I started in this business every female that could be bred was bred -- it was a given. Prices demanded no less, really. Now, we know better than that, but the big question at the first Ohio State Camelid Conference in 1998 was "when do I start breeding my females?" And, while there were those that demurred, the general consensus among people who had more experience was "100 pounds or a year of age, whichever comes first." We were even handed the argument that, even if the female has some growing to do, her calcium stores would not be necessary for the cria until the final trimester. Well, as with so many "rule of thumb issues" that is patently untrue, based on mine and others' experiences. Moreover, I see females that mature at 18 months and are just plain ready, I see some that can wait to three years of age before they are receptive to breeding. There is both physical readiness and emotional readiness. And when it comes to when the males are ready, I think Mother Nature has a very nasty sense of humor because every fiber quality male seems to know precisely what to do and is willing to do it long before your best males even "get" why a bunch of females are dropping at their feet! If you have ever experienced a gate being left open that separates males from females, you know what I am talking about. That said, I have seen males start at 16 months and they settle females pronto, and I have seen guys at two years of age going through the motions with gusto and they are not settling females, but five months later, they turn into the five minute wonder breeders that catch a female in a single breeding, time after time after time. I have also had many males that waited until they were three years of age, and I can think of one very famous import male that did not start breeding until age six -- and admittedly that six year outlier is not one I would like to have to experience or consider breeding into my lines. I think the principal take-away from this is that alpacas are all INDIVIDUALS, and good things will come to those that wait.

|

|

Saturday, January 24, 2015

A gentle snow is falling here, and all the tree lines, fence lines, barn roofs are featuring softened edges. Postcard images of New England in winter are the order of the day here. So, I am at my computer and musing about fleeces, once again.

As someone that has focused primarily on production of elite whites and lights over more than seventeen years in alpaca breeding, I think it is time to discuss the wide range of “first fleeces” on crias, as these come in a wide array of styles that bear mention. Fleece improvement throughout the range of natural colors, too, will mean that what those of us with light herds are very accustomed to seeing will also be more prevalent across that spectrum of color with time. It is difficult to explain to the newcomer to alpacas that, after waiting nearly a year for that cria to arrive, they might have to wait for the second fleece before they have anything to crow about, but that can be the case many times. While I am the first to admit that patience is not my strong suit, I urge new breeders to cultivate some patience in the fleece department, as they will need it.

They Have It All: This is the kind of fleece that you almost pinch yourself and probably part daily, just to assure yourself that ‘they still have it.’ Everywhere you part this fleece, it exhibits all the qualities, from uniformity (of micron, of crimp style, and so on). Part on the belly, and it’s there, go up the neck, down the leg to the fetlock – good grief. If you shear such an animal down as a cria, expect a newcomer to the industry to say it looks like that animal has a chenille fleece when the regrowth appears. This is truly the good stuff. These cria tend to do well even when shown as juvies.

Well, This Has It All, But Why Does It Look Like a Suri and I Am Just Not Sure It’s Dense: Brightness bordering on luster, pencil-like staples that tend to hang down in tight tiny fashion. Watch this animal! You may decide that, over the years, this is THE fleece you love most in your barn. First of all, it is displaying an architecture that, with time, may give way to a They Have It All fleece, or it may stay as it is. I have to admit, I get these fleeces as first fleeces a great deal, but they tend to morph into They Have It All fleeces on the second fleece. Some people are more fortunate and see this fleece for multiple shearings. We usually feel an almost greasy hand to a fleece like this, as opposed to a “cottony” hand, giving us the feeling that maybe the sebaceous glands are more prevalent in this fleece. We also talk about a lower scale that causes the extreme brightness. Some dare call these SILKY. So far, despite fiber testing, we have not found a means of distinguishing these from the “They Have It All” fleeces in terms of an actual test. However, if you process a fleece like this by hand, you will note that it does process – just like silk, and it has very little static associated with having been processed, regardless of the low micron of the fiber. Now, in some cases, animals with these sorts of first fleeces do well in both halter and fleece shows, but not all do.

Well, I Swear He/She Had It, But He/She Seems to Have Lost It: When a cria sports this fleece style as a newborn, this one excites you just as much as the ones that have it all. But extremely fine cria fleeces do not always retain that initial corkscrew-like appeal and may grow out into what some of us call the “cria flats,” which is to say the fleece goes quite straight. Fear not, as messenger angels tend to say. Instead, look at the staples and note if they have a great deal of independence, or absence of cross-fibering. Are there whisper-width “tufties” protruding across the blanket? Some of these young animals actually do redevelop crimp from skin to tip with time prior to the first full shearing. Some won’t at all, but oh, wait until that second fleece grows in, as it will take on far greater eye appeal! Taking such an animal to a show in its first fleece can be a disappointment, but if you wait until they are yearlings, people will ask you why they have never seen this animal before.

I Just Don’t See Anything In That Fleece: Whether or not you shear it down when this animal is a cria or whether you simply leave it be, you just don’t see any crimp, but you do see almost a suri-like pencil quality to each staple and they are quite tiny and tend to hang down, as a suri might, albeit in a slightly more fluffy fashion. Those with this style, even shorn down, appear to have a very slight wave usually but brightness that really borders on luster. Here again, this is one of those “second fleece phenom” varieties. Give them time, and if you don’t believe me, ask anyone that has opted to sell a male with this fleece as a fiber animal while it is less than a year old.

Now, there are fleeces that, regardless of the care you take in matching the fine qualities of your “stud females” to a fabulous male that can support all that female’s great qualities and improve on that aspect you think needs a tweaking, the resulting offspring just may not be as great as you expect. In fact, beware of anyone that tells you that he/she never produces pet quality animals in his/her breeding program! This less than satisfying result can be due to almost anything, from the pure vagaries of livestock breeding to fetal development issues when the cria is developing the number of follicles. Moreover, sometimes a truly phenomenal dam with excellent qualities can be a “one percent of the Bell Curve” result and, regardless of the qualities of the stud to which she is bred, may never recreate herself, much less produce an improved offspring. You have done the very best that you can, and you won’t be the first to have this happen.

|

|

Friday, January 9, 2015

Fleece is the most important characteristic involved in breeding alpacas, after sound physical structure. We know that the pre-Incan civilization selected for fleece on alpacas and with llamas they selected for their ability to act as beasts of burden. From archeological records, we also know that these pre-Incans had some mighty amazing fleeced alpacas. Now, there are a dazzling array of fiber statistics that are used to entice potential buyers. My suggestion is that, when handed a histogram, peruse the website of the testing lab that produced that histogram. These labs all make a great effort to ensure that people on the receiving end of their histograms can understand (1) testing methodology employed and (2) the meaning of each term applied to a fiber sample. One thing to keep in mind about a histogram, regardless of the testing methodology is that this is taken by the breeder from what is supposed to be the “mid-side” of the fleece. That can mean a busy shearer hands that sample to the breeder, or the breeder picks his/her version of mid-side, and so on. For this reason, I am one that prefers to look at the entire fleece, if shorn, and will do a thorough search across the animal if the animal is in full fleece. I like to think of a histogram as a potentially valuable compass point on a map, and I liken the entire fleece to the map itself.

Recently, someone posed a question on an alpaca forum asking people to list in order the fiber traits that they most desire/breed for. The list included the following:

fineness

density

uniformity

length

crimp

brightness/luster

handle

I contended in my short answer that I could not provide a purely ordinal ranking for the simple reason that I believe some desirable fleece traits are symbiotic and tend to show up together.

However, I will attempt to order fleece characteristics as they apply to my selection criteria.

Unformity: Simply, my first and most important characteristic is uniformity, provided this means uniformity of the average fiber diameter. As someone that sorts through a blanket fleece in its entirety, finding multiple grades of fleece in one blanket makes the process of deciding on a ‘best use’ of the fiber more difficult. Moreover, the more uniform the grade is across the entire blanket fleece, the better the HANDLE of the fleece. After all, when people new to alpacas just feel their fleece, they remark about how soft it feels! When I talk about grade, it’s not a “feel” thing, it is an “eye thing” yet getting it right with the "eye" can lead to a “feel good” thing!

Fineness: Fineness is a laudable goal as well and is even better if that animal’s fleece is uniform in grade. I purposely add older stud males to my breeding program that display fineness at an older age in the hopes that we can achieve lasting fineness in our breeding program. My top females in my barn are able to have crias yearly yet produce grade 1 or 2 fleeces (Grade 1 is under 20 microns, and Grade 2 is 20-22.9 microns) each year. You can call this quality lasting fineness or genetic fineness, but whatever, it is a prized characteristic in breeding stock, particularly since hormonal changes can coarsen fleeces.

Fleece Architecture: After this, I look for architecture to a fleece. Now, that includes a bundle of traits that I see working in a symbiotic fashion. Basically, I am looking for as much independence of individual staples as possible, preference that such staples are tight and have “heft” when placed between my thumb and index finger. I expect such a fleece to exhibit cohesiveness, as in it stays together if picked up (I like to say that you can sort a cohesive fleece out of doors in a gale force wind without any of it blowing away sometimes). I look for primary fibers (they are shinier than secondary “wool-like” fibers) to have character/crinkle such that they match secondary fibers. Sometimes, this characteristic can also lead to parity of fiber diameter between primaries and secondaries. I have also observed that, the more the fleece staples are tightly arrayed, the more likelihood that such fleece will exhibit a desirable brightness in addition to a very tactile crimp. Other things can affect brightness, but I will leave that for a future discussion.

Staple Length: I consider staple length to be an outlier trait but one which obviously contributes to fleece cutting weights and once we achieve quality fleeces, the more we can produce, the better. Over time, most animals’ staple does decline, and many that retain exceptional fineness over the long haul are observed to have a back-off in staple length occur more rapidly than animals whose average fiber diameter creeps up with time. We commonly hear of a trade-off in staple length with lasting fineness.

Density is one of those elements that is most difficult for many people to gauge. Apparent density is not density, and even in the show-ring, exceptionally fine animals with excellent density are referred to as “the finest in the class yet lacking the density of the animals standing ahead of him/her.” Not always, but it does happen! I remember when I was told that if you select for density that you will get fineness along with it in the bargain. It would be great were that the case. But that is a “sometimes” proposition, I think.

Crimp: Admit it, we all love crimp. A bright fleece with very defined crimp can leave even some of the best fleece sorters agog. There are a few things about crimp, though. Animals that exhibit a very high frequency crimp in younger years may have a less high frequency crimp as they age and, guess what, the average fiber diameter is also creeping up. Another thing that can occur is that organized staples become less organized with time.

Now, for some eye candy, because everyone loves eye candy!

|

|

Thursday, October 23, 2014

Brillanta

Now that I know we have a classic Nor’easter bearing down on our neck of the woods, I have some time to commit some of those thoughts I have always had about alpaca breeding to virtual print form.

I always encourage prospective new breeders to keep visiting as many farms as they possibly can fit into their schedule, and you might ask why. I sincerely would hope that people that take up alpaca breeding in all seriousness develop a set of “must haves” that would make up that ‘total package alpaca’ before they plunk down hard-won money to buy their initial foundation herd. Put another way, I think any serious breeder needs to be able to visualize, in his/her own mind’s eye, the ideal animal of whatever livestock they breed. I have written this before, but there is only one time that a breeder can select for a multiplicity of variables, and that is when he/she is acquiring breeding stock! Once those animals are in his/her barn, it may be possible to upgrade one to two traits through breeding – and obviously, we are talking about dams here. Males are a topic unto themselves.

Now, there are many business models being developed in the alpaca community, and many of them will not be dependent on developing an eye for what one views as an outstanding alpaca. Fiber production farms may desire an animal with good physical structure so that it is functional for the long haul, but the primary focus will be on fleece characteristics that meet their demands for end-product. There are agri-tourism-based alpaca farms now where the alpacas are part of a pleasant distraction for visitors touring the farm. Each alpaca business model is founded on a set of strategies and goals. There are yet other hybrid alpaca business models.

My ideal alpaca is more compact in frame, but even if larger in frame, the alpaca will possess smooth, fluid movement and a certain elegance of proportion that conveys an overall balanced, aesthetically pleasing appearance. I like an alpaca that looks solidly rooted on terra firma – excellent “chi.” I look for what I call good circumference of bone, if you like, since to my knowledge no one has performed extensive bone density studies in camelids. In the scheme of things, headstyles may seem unimportant, but a deep broad but short muzzle and a head with a dense woolcap happens to be a preference of mine. I look for the neck to be an organic extension from the chest, upright set to neck. I suppose humans must find 90 degree angles pleasing, but I do like a topline that is straight and remains so when the animal is in motion. Head/neck, trunk and legs viewed from the front should be as close to 1:1:1 ratio as possible. Visualize the length of the head/neck imposed on the topline and it should be no more and no less than 2/3 of the length of the topline. I like broad chests, excellent spring of rib and a straight plumb-line to the legs. Angulation of rear legs at the hock is important. I watch an animal track from behind and pay close attention to see that hocks do not rub while the animal is moving and, of course, if an animal rope-walks in the rear, that is highly undesirable. Bear in mind that conformation has a very low coefficient of heritability. Some people will say that, in that case, one cannot breed for it. My view is that, to do the best job possible as a breeder, both sire and dam should have excellent conformation. Okay, I should say a little about bites here. Some believe one cannot breed for correct bites, but I do believe one can and should try. There is more to a bite than the incisors that are the focus of the show-ring. The side bite must knit together properly, or the alpaca is compromised as to its ability to chew a cud. Incisors should be at a 45 degree angle and I actually prefer them to be just shy of the bite plate. Such a bite usually requires no maintenance.

Fleece is, of course, a very important element. I feel my first order of business is to produce alpacas with uniform average fiber diameter fleeces as, without a goal of uniformity, grading of fleece for proper end-use will be more of a chore. Fineness – and in particular lasting fineness – is an overarching goal as well. Now, I also seek out a certain fleece architecture that includes very little cross-fibering between the individual staples – and the smaller the staple the better, but it still must feel like something when pressed between thumb and finger. I prefer a crimp style that I call “crimp squared,” as frequency and amplitude are both high. The more organized the fleece, the brighter the fleece can be and ease of parting the fleece “like a book” is enhanced, or so it seems to me. Now, there are many fiber statistics that can be brought to bear and these are useful. I challenge people to learn to gauge grade of their alpacas’ fleeces. I look for a cohesive fleece that you can shake out of doors in a gale force wind, and it remains in one piece. Density is a very key component, but I view staple length as possibly the most important variable in improving overall fleece yields. Unless I build to suit from my own program, I tend to acquire males that are five years or older that still have fleeces that could be shown. I am less likely to breed to that newest multiple champion male if I have the option to breed a female to his sire. So, okay – if I produced him in my barn, you better believe I will use him!

Pedigree does matter in my program. I will say very little about it here, except that it is a starting point for me when I am researching an animal. There are very few true impact sires in the alpaca breeding business, and only a few males have more than 100 offspring. It begs the question whether or not we know all that much about even some of the most well-known males in the US and their true abilities – and if we do not know what some of those well-known males could do, imagine how little we know about the dams!

Breed standard(s) again are a topic of discussion among the alpaca breeding community. What is old is new again, as they say. I believe that, regardless of adoption of a breed standard, a concept of one’s ideal alpaca is a vitally important aspect in developing a breeding program and grounding one’s strategy. You may never find your ideal alpaca, and you may also find that ideal alpaca changes with time.

Casanova, Dually, Pundit

Dually Noted

Accoyo Goodfella

Bonhommie

|

|

Wednesday, October 22, 2014

Suri on a Rainy Night!

Despite the dreary weather, we continue to prepare our farm for the eventual onset of winter. We are busy getting wood for the woodstove, resurfacing barns, figuring out when and where that next hay delivery is going to go. Now, we can see the several days of rain in a number of different ways. For one thing, provided one of our local hay suppliers planned for it, these are good soaking rains that will help them cut a third cut of hay, and wouldn't that be a wonderful thing! Once you are a seeker and admirer of quality hay, third cut hay is almost the holy grail in our Granite State, where the micro-climates can dictate so many variations on weather as to make the most intrepid meterologist tear his or her hair out!

Alpacas approach wet weather somewhat differently than humans, who usually prefer to accomplish the work that must be done outside and retire to the inner sanctum for some wool-gathering. Okay, admit it -- rainy days are also exceptional napping weather. I notice the alpacas prefer a good soaking rain to one that just makes the outer layer of their fleece wet and might tend to insulate and make them warmer than they would like to be. So, on a day like today, they will likely spend more time in the pasture than they do on the most gorgeous sunny days. Now, of course, these are just my observations, and I am not an alpaca nor do I play one on a sit-com!

Our latest cria, Zenyatta, who lives up to her namesake as much as any alpaca could, proved that she could fare as well on a wet track as on a hard, fast track, today. She continues to lap our largest pasture and is not impressed in the slightest that she is surrounded not only by adult alpacas but also by some imposing suri llama females.

Now, rainy days do not make for great picture-taking weather for huacayas, but suris are quite another story. So, when the weather clears, I will be out taking pictures of the huacayas. Check back when the sun is shining again!

|